This article was first published in Voice Male magazine.

My son Zach grew up exposed to many opportunities. He played baseball, basketball. football and piano. sang in choir and performed in church musicals. As the father of a son, I was especially delighted he was athletic. I got him private pitching and batting lessons, enrolled him in basketball and football camps. Zach excelled in all three sports, while at the same time demonstrating talent in non-athletic “side” projects. It all seemed picture perfect; he had snips, snails, puppy dog tails, and some sugar and spice, but not everything nice. I had me a boy that would make any father proud.

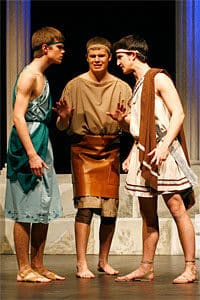

After Zach‘s football team won the state championship in his junior year, he told me he was quitting basketball to focus on drama and ballet instead. Once again, I was perplexed. Theater is great. I enjoy it. I support it. But, if you‘re a guy and you‘re good at basketball, you don’t quit it for theater. In theory, I was supportive of a society that allowed men to develop their full humanity, but emotionally I held on to wanting the alpha son—the athlete. Nevertheless. that winter, instead of racing down the court. Zach danced his way across a stage sporting a tutu in Carnival of Animals and pontificated while wearing a toga in Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors. He continued to work on singing, dancing and acting in hopes of getting a lead in the next school musical. What was next to go? I lamented. Football?

With the season over. Zach put away his cleats, grabbed his dancing shoes, and auditioned for Grease at the local community theater, competing against the city’s theatrical elite. He got a part in the chorus where, for I8 performances, he was able to grow and shine. And then. in his final year of high school. Zach’s goal—to get a lead in the school musical—was realized: he was cast as Ozzie, the sailor in On the Town. He danced. sang, joked, and lit up the stage. I was amazed. I had begun to understand the courage and wisdom in my son’s choices.

This is not our fathers’ world where only finely tuned aggression, competition, and toughness help men rise to the top in business or politics while also becoming successful partners and parents. In order to thrive today. men and women need to develop their full selves, unconstrained by outdated gender roles. Doing so helps cultivate the environment needed to succeed in personal relationships in a diverse and changing world. Of course I knew all this theoretically and professionally but it took Zach to teach me this emotionally.

Zach was as much or more healthy a man wearing a tutu and singing and dancing on a theater stage as when he blocked and caught passes on a football field. His courage to do both makes him. in my mind, a remarkable human being.

“Zach, my son, you the man.”

Interesting to hear part of this testimony. Throughout many observations, as well as my own experiences, I have noticed that it is much harder to emotionally condition yourself, rather than simply conditioning a new behavior. I have also noticed, throughout observing my own behavioral tendencies, that if I can emotional condition myself I will accomplish more fulfilled and permanent rates of change. I think this has much to do with why addicts fail to change even though they know they need to. What ever it is they are addicted to, often gets deeply associated with such a positive emotion making it so they don’t emotionally desire a change however; they may even know/believe they should/need to change. Its the whole, can’t change unless you want to even though you need to conundrum.