In their 2014 book “Mascupathy: Understanding and Healing the Malaise of American Manhood,” co-authors Charlie Donaldson and Randy Flood pointed to the gendered nature of mass shooters. They called for a recognition of this distinction and a public health policy to address and help prevent further tragedies. And yet, here we are in 2021, still with a nameless social problem and no public health policy to address it. While we can choose to blame the recent mass shootings on the pandemic, hate crimes, or divisive politics, the foundational question Donaldson and Flood asked in 2014, “Why is there seemingly a conversation about everything else but men and masculinity?” remains unanswered. What was true then, and remains true now, is that by choosing to not see and discuss the gender of male shooters, we are also refusing to elevate conversations about men’s mental health in our discussions about public health and our vision for a less violent future. In 1963, Betty Freidan made a bold and unheard-of claim that we had “a problem with no name” regarding the mental wellness of females in our society. Decades later, we have “a problem with no name” regarding the mental wellness of males. The same attention and focus placed on the mental health of women in our society needs to be given the males in our society as well. In 2014, Donaldson and Flood stood on the shoulders of other prominent contributors in the men and masculinities movement to provide both a societal vision and counseling programs to help males revision masculinity and reinvent manhood into a more humane version. Seven years later, perhaps we’ll find a way to help men reclaim their humanity and, at the same time, end the increasing death toll caused by male mass shooters. Here is an excerpt from that book:

The Malaise of Men

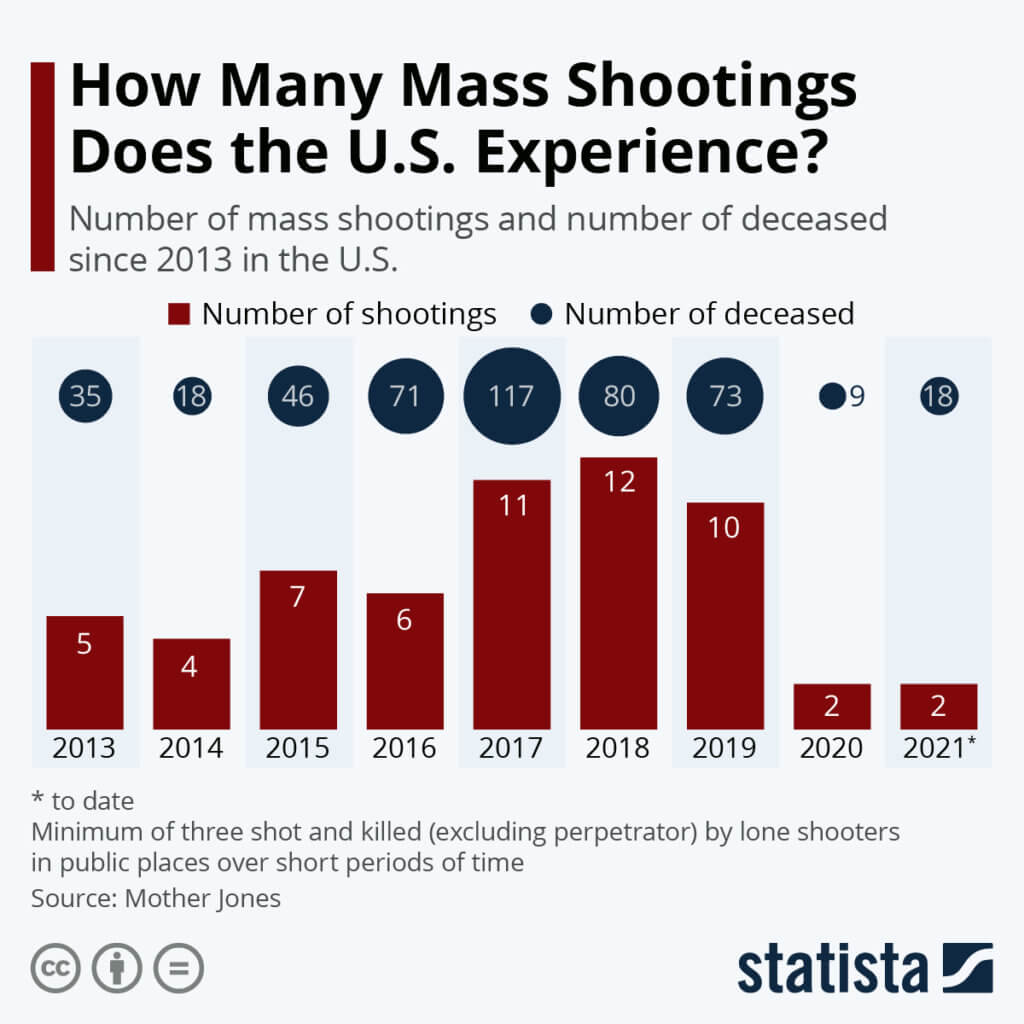

In September 2013, Aaron Alexis shot and killed a dozen people at the Washington Navy Shipyard. The previous year, there were seven horrific shootings perpetrated by seven lone killers: Andrew Engeldinger, Wade Michael Page, Ian Stawicki, One L. Goh, James Holmes, Jeong Soo Paek, and Adam Lanza. After each mass shooting, the national conversation focused on gun control, the murderers’ mental health problems, the role of the Internet and, sometimes, extreme religious beliefs. These are all important issues, but there’s something missing from the conversation. Something else that demands attention. What did the shooters have in common? Many may have been diagnosed as mentally ill. They may have shared an interest in weapons and/or violent video games. What is most obvious and indisputable is: the shooters were all men. In fact, according to Mother Jones magazine[*], in the 31 years between 1982 and 2013, 66 of 67 mass shooters were men.

Tens of millions of women are diagnosed with mental illness, and a good many of them like guns, but in the last 30 years only one has become a mass shooter. What’s going on with the men who shoot and maim innocent people? Why, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), are an estimated 1.3 million women victims of physical assault by an intimate partner – usually male – each year? And why do men in the United States, as Will Courtenay writes in Dying to be Men, engage in more risky behaviors, suffer greater numbers of preventable health conditions, and die more than five years earlier than women? Beyond what they do to each other, women, and children, men struggle with their own psyches. CDC statistics report that they kill themselves four times more frequently than do women. Why is there seemingly a conversation about everything else but men and masculinity?

For years we have asked ourselves: why do concerned and thoughtful men and women overlook the reality of male violence? Probably because the pervasiveness of male aggression reinforces the social narrative that men will behave badly. The result? Pundits, government officials, the media, and the general public unwittingly all collude to accept men’s violence in a grand version of “boys will be boys.” Instead of being viewed along the lines of epidemics and viral outbreaks, which can be treated, men’s acts of mayhem are reported in the same manner as hurricanes and tornadoes – inherent in the nature of things.

A Touchstone for a Greater Malaise

We cite the gender of the shooters because it is a bellwether for the more common problems of contemporary American manhood. What we have discovered in our years working with a wide range of men is this: many aspects of their lives influence their thinking, feelings, and behavior including genetic make-up, family of origin trauma, and cultural and economic backgrounds. The one common factor is the role of masculinity – in particular, the socialized drive that virtually all men share to be tough enough, stoic enough, strong enough, man enough.

As different as shooters are from “regular guys,” their similarity lies in their exposure to male socialization; their difference lies in their response to that exposure. While there is no doubt some men who come into schools, mosques, and movie theaters to shoot are sociopaths, often they’re also men whose shame and self-contempt for not being adequately masculine enough is all-consuming. Typically, they have been repeatedly bullied or marginalized by other men, and their obsession with proving their masculinity morphs into compulsive and misplaced retaliation perpetrated on both bullies and innocent bystanders.

In the act of killing, they see themselves becoming the quintessential macho man who takes no prisoners. They replicate the image of the strong, tough guy – a “winner” portrayed in movies and video games striding triumphantly across a field of bombed-out buildings and bodies.

A Wake-up Call

We write about male shooters not because they have much in common with ordinary American men – they don’t – but because shooters are our wake-up call. As murderers, they are the most extreme example of what happens when a man’s struggle to be “man enough” fails. Unwittingly perhaps, they invite, no, demand, we pay attention to the role of masculinity and male socialization in American society.

Shooters are like the canary in the coal mine warning us to pay attention, to dig deeper in our efforts at understanding men. For example:

- Why do two men aggressively jockey for pole position as the road narrows and then dangerously try to out maneuver one another on down the highway?

- Why does a guy diagnosed with cancer refrain from telling anybody about his condition and demand that his wife follow suit?

- Why, if you ask a man what he’s feeling, does he just continue with the story, oblivious to its emotional component?

- Why do college buddies who get together after 20 years ignore two decades of touching stories of triumph and disappointment only to spend an evening in hollow banter?

Men Can Change

We live in an age that cherishes personal transformation. Popular culture is replete with stories of reinvention and resocialization: juvenile delinquents turn into good citizens, sinners are reborn, and bigots renounce their hateful attitudes.

Beyond the failure to see that the problem of men is their distorted masculinity, the possibility of rehabilitation is generally ignored. The assumption that the psyche of the male persona is intractable has been rigidly embedded in our national consciousness. But we know that men can and do change. We’ve seen them do it.

In summary, we believe that the majority of men are good guys. We write about their limitations – their dark side – to explain the struggle of masculinity. We describe their inner brawls and their daily skirmishes with other men and women because we believe that most men are inadequately aware of their psyches and restricted in their relationships, and because we are convinced that understanding will bring change.

[*On March 22, 2021, Mother Jones updated this number to reflect the range of years 1982 – 2021. The new total 121.]

Leave A Comment